Ankle Fusion (Arthrodesis)

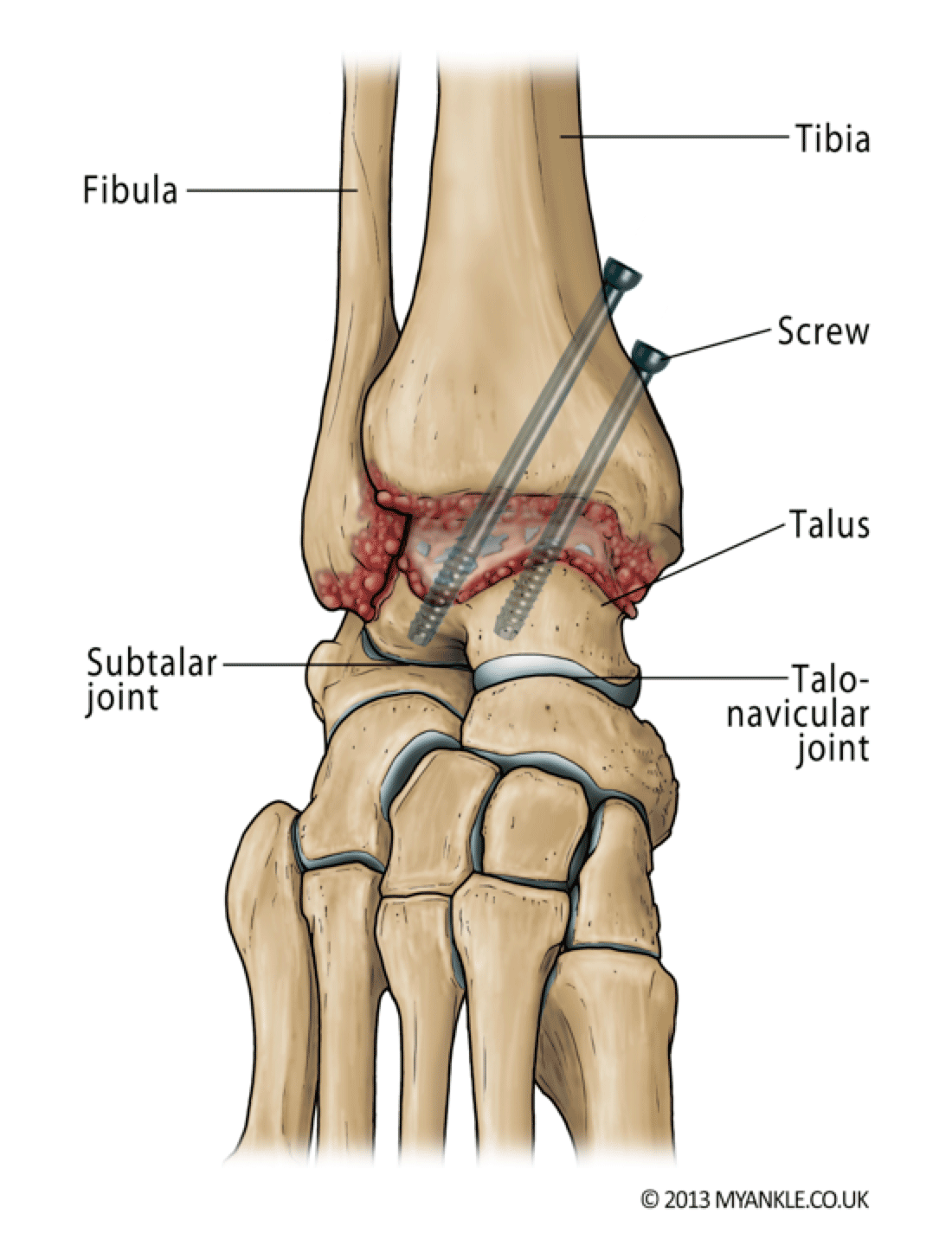

Ankle fusion is an operation to convert a stiff painful joint into an even stiffer but painless joint. In this procedure, the remaining damaged cartilage is removed from the ends of the bone and the two bones are then held together in compression using screws, or plates until they join to become one (bone fusion).

Ankle fusion affords excellent-pain relief and good function.

A variety of techniques are available to achieve a stable fusion, including arthroscopic (keyhole surgery) and open surgery. The most common technique in the UK is arthroscopic ankle fusion where the joint surfaces are prepared through a telescope and two or three screws are inserted through small incisions, going across the joint to hold the two ends together.

In complex deformity or where the subtalar joint (the joint below the ankle) is also affected, a tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) intramedullary nail might be necessary.

Ankle fusion does have its limitations including prolonged immobilization and the risk of non-union (the bones not knitting). Because the ankle joint has been stiffened, more stresses will be taken by adjacent joints which are at risk of wearing with time (adjacent-joint arthritis). X-ray features of adjacent joint arthritis are common after 10 years, but not all patients will require treatment for this.

Biomechanical studies have shown that ankle fusion increases contact stress at the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid Joint. At 44 months follow-up, following ankle fusion, patients demonstrated reduced cadence and stride length accompanied by a diminished range of motion of the hindfoot and midfoot during walking.

In a study of 28 patients who all stated they were highly satisfied immediately after ankle fusion, 79% reported difficulty walking on uneven ground, and 64% reported aching around the ankle with prolonged standing or walking.

Post Op

This video shows a man 1 year post arthroscopic ankle fusion. He is able to stand on his tiptoes and jog, albeit with a slight limp.

Are there many major risks with ankle fusion?

In addition to the general risks of ankle surgery, the specific risks of ankle arthrodesis relate to problems with union and transference of stress to the adjacent joints.

Mal-Union: Research has shown that 5 to 10% of fusions do not heal in the exact position intended. This may either be due to the fact that the position was not achieved at the time of surgery or that the bones have shifted while in plaster. This does not usually cause any major problems but rarely further surgery may be required to correct this.

Adjacent Joint Arthritis: Because the ankle joint has been stiffened, more pressure will be taken by adjacent joints, which, with time, are at risk of wearing . Signs of arthritis in the adjacent joints are common on x-rays after 10 years, but many patients do not require treatment for this.

Need for Further Surgery: Sometimes the screws become prominent under the skin. If this happens, they can be removed but only about 1 in 10 patients need the screws to be taken out. If screws need removing, we usually advise you to wait at least a year after surgery to give the bones time to become strong.

General complications following ankle surgery:

Swelling – you should expect some swelling for up to one year after surgery. Elevation of limb above heart level for the first two weeks helps to reduce swelling and aid wound healing. If swelling persists and you are concerned, seek medical advice.

Bleeding – all wounds bleed after surgery, but rarely this can be excessive causing wound problems or requiring further surgery.

Painful scar – any type of surgery will leave a scar. Some people develop larger scars than others. Occasionally this can cause pain and irritation. If you suspect you are prone to scar problems please discuss this with your surgeon prior to surgery.

Infection – superficial wound infection (redness around the wound) occurs in up to 5% of cases. Much rarer (less than 1%) is a deep infection where the metalwork or bone is infected. Minor infections usually clear up with a course of antibiotics. More serious infections may require further surgery and involve complex and lengthy treatment.

Nerve injury – numbness or tingling at the surgical site is common and is usually temporary, but up to 50% of patients who have an ankle replacement or open ankle fusion will get some numbness on the top of their foot. This is not usually a problem. If a key nerve is injured (up to 1.5% of cases) then it can cause permanent numbness and shooting pains requiring medication or further specialist input. Rarely the sympathetic nerves (also known as fight or flight nerves) react badly after the surgery, and cause temperature and colour changes to the skin – this is known as complex regional pain syndrome (less than 3%) and can take up to 12-18 months to settle. Occasionally it does not settle and causes long term pain.

Problems with union – occasionally in arthrodesis bones fail to unite (fuse) and in the case of a replacement, the bones may not knit to the implant. This can happen in up to 10% of patients. If you smoke, your risk of such a complication is greatly increased. You will be advised to stop smoking before surgery.

Blood clots – deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is uncommon (5%), and pulmonary embolus (PE) is very rare (less than 0.5%) and occurs due to blood clots. We do everything to minimise these risks but they can occur and can be serious causing prolonged leg swelling or chest problems. Blood-thinning medication may be given to prevent blood clots whilst in a cast as well as a special stocking on the other leg to improve venous circulation.